Slechts een paar dagen voor mijn 65e verjaardag begon ik de drie delen van “De Tao van Seneca” te lezen. Ze zijn gebaseerd op de “Morele brieven aan Lucilius” van Seneca, naar het Engels vertaald door Richard Mott Gummere. De compilatie is van Tim Ferris en er zijn commentaren van moderne stoïcijnen aan toegevoegd.

Ferris in zijn voorwoord: “Ik geef De Tao van Seneca weg in de hoop dat het je leven verandert, en ik beloof je dat dat kan.”

Hier maak ik aantekeningen terwijl ik de brieven lees in de volgorde waarin ze in het boek staan.

Maar eerst enkele opmerkingen over de brieven zelf:

Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium

De Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium (Latijn voor “Morele brieven aan Lucilius“), ook bekend als de morele brieven en brieven van een stoïcijn. Het is een verzameling van 124 brieven die Seneca de Jongere in de laatste drie jaar van zijn leven schreef. Daarvoor werkte hij ruim tien jaar voor keizer Nero.

Seneca richt zijn brieven aan Lucilius Junior, de toenmalige procurator van Sicilië, die alleen bekend is door Seneca’s geschriften. Ongeacht hoe Seneca en Lucilius feitelijk correspondeerden, het is duidelijk dat Seneca de brieven schreef met een breed lezerspubliek in gedachten.

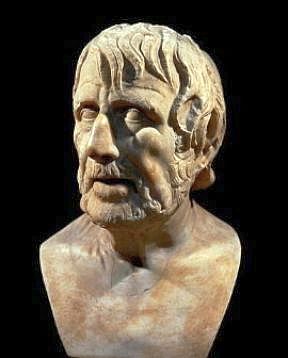

Seneca

Hij begint vaak met een observatie over het dagelijks leven, en gaat dan verder met een kwestie of principe dat uit die observatie is geabstraheerd. Het resultaat is als een dagboek of een handboek met filosofische meditaties.

Alle brieven beginnen met de zinsnede “Seneca Lucilio suo salutem” (“Seneca begroet zijn Lucilius”) en eindigen met het woord “Vale” (“Vaarwel”). In deze brieven geeft Seneca Lucilius advies over hoe je een meer toegewijde stoïcijn kunt worden.

Hoewel ze Seneca’s persoonlijke stijl van stoïcijnse filosofie behandelen, geven ze ons ook waardevolle inzichten in het dagelijks leven in het oude Rome.

Deel 1 van de Tao van Senaca bevat zijn eerste 65 brieven. Dus laten we beginnen!

Over tijd besparen

- Terwijl we het uitstellen, snelt het leven voorbij.

- Niets, Lucilius, is van ons, behalve de tijd.

- Ik beschouw een mens niet als arm, als het weinige dat overblijft genoeg voor hem is.

Over discursiviteit bij het lezen

- De belangrijkste indicatie, naar mijn mening, van een goed geordende geest is het vermogen van een man om op één plek te blijven en in zijn eigen gezelschap te vertoeven.

- Wees echter voorzichtig dat het lezen van vele auteurs en boeken van welke soort dan ook de neiging heeft om u discursief en instabiel te maken.

- Overal betekent nergens.

- Omdat u niet alle boeken kunt lezen die u bezit, is het daarom voldoende om slechts zoveel boeken te bezitten als u kunt lezen.

- Vraagt u zich af wat de juiste grens is voor rijkdom? Het is in de eerste plaats om te hebben wat nodig is, en in de tweede plaats om te hebben wat genoeg is.

Over ware en valse vriendschap

- Als je een man als een vriend beschouwt die je niet vertrouwt zoals je jezelf vertrouwt, vergis je je enorm en begrijp je niet voldoende wat echte vriendschap betekent.

- Het is net zo verkeerd om iedereen te vertrouwen als om niemand te vertrouwen.

- Je moet in ieder geval al je zorgen en reflecties met een vriend delen. Beschouw hem als loyaal, en je zult hem loyaal maken.

Over de verschrikkingen van de dood

- Niemand kan een vredig leven leiden als hij er te veel over nadenkt om het te verlengen, of als hij gelooft dat het doorstaan van vele consulschappen een grote zegen is.

- De meeste mensen bewegen heen en weer in ellende tussen de angst voor de dood en de ontberingen van het leven; ze zijn niet bereid om te leven, en toch weten ze niet hoe ze moeten sterven.

- Geen enkel goed ding maakt de bezitter ervan gelukkig, tenzij zijn geest verzoend is met de mogelijkheid van verlies; niets gaat echter verloren met minder ongemak dan dat wat, wanneer het verloren gaat, niet gemist kan worden.

- Geloof me op mijn woord: vanaf de dag dat je werd geboren, word je daarheen geleid (red: naar je dood). We moeten over deze gedachte nadenken, en over soortgelijke gedachten, als we kalm willen blijven terwijl we wachten op dat laatste uur, waarvan de angst alle voorgaande uren ongemakkelijk maakt.

Over het delen van kennis

- En inderdaad dit feit (red: dat er geen elementen meer in mij zijn die veranderd moeten worden) is het bewijs dat mijn geest veranderd is in iets beters; dat het zijn eigen fouten kan zien, waarvan het voorheen onwetend was.

- Niets zal mij ooit plezieren, hoe uitstekend of nuttig ook, als ik de kennis ervan voor mezelf moet houden.

- En als mij wijsheid werd gegeven onder de uitdrukkelijke voorwaarde dat het verborgen moet blijven en niet mag worden geuit, zou ik het weigeren.

- Geen enkel goed ding is prettig om te bezitten, zonder vrienden om het te delen.

- De levende stem en de intimiteit van een gemeenschappelijk leven zullen je echter meer helpen dan het geschreven woord.

- Mannen vertrouwen meer op hun ogen dan op hun oren.

- De weg is lang als je de voorschriften volgt, maar kort en nuttig als je patronen volgt.

- Plato, Aristoteles en de hele menigte wijzen die voorbestemd waren om ieder zijn eigen weg te gaan, haalden meer voordeel uit het karakter dan uit de woorden van Socrates.

- Wat mij vandaag beviel in de geschriften van Hecato; het zijn deze woorden: “Welke vooruitgang, vraag je, heb ik gemaakt? Ik ben een vriend voor mezelf geworden.”

Op menigten

- Vraagt u mij wat u vooral moet vermijden? Ik zeg: menigten; want vooralsnog kun je jezelf niet veilig aan hen toevertrouwen.

- Sluit je aan bij degenen die een betere man van je zullen maken.

- Verwelkom degenen die u zelf kunt verbeteren. Het proces is wederzijds; want mannen leren terwijl ze lesgeven.