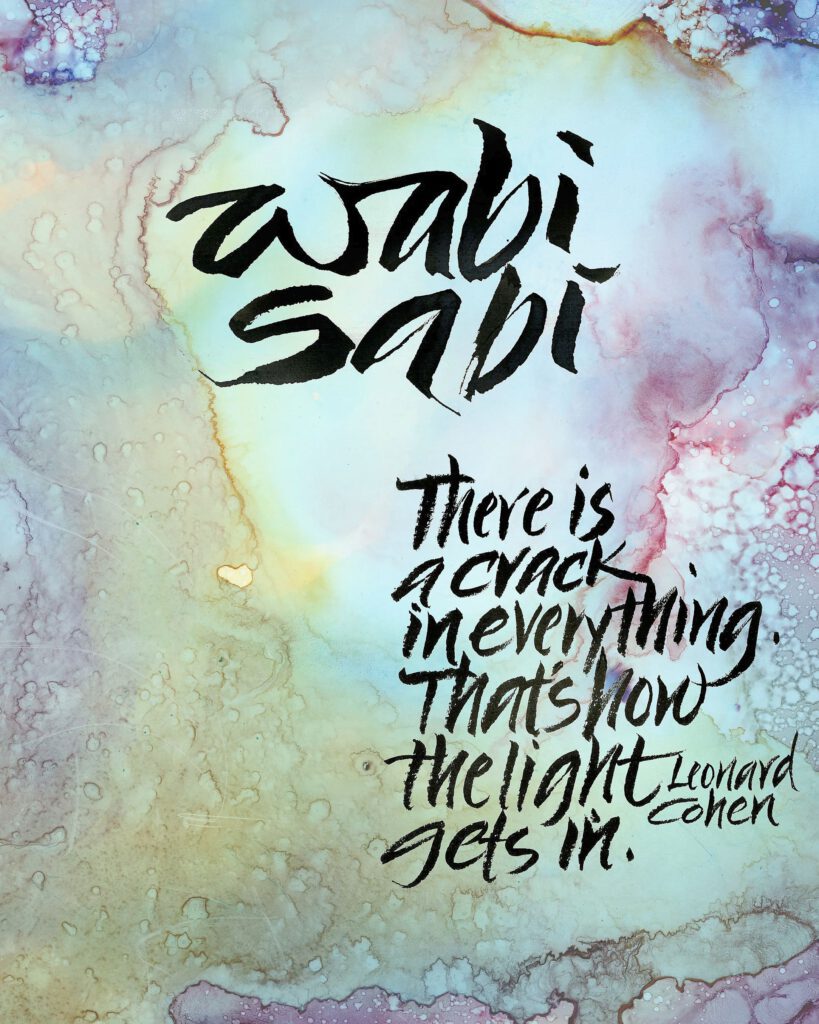

Ergens hoorde ik over het Japanse idee van wabi sabi, en wist niet wat het was, totdat ik de uitleg van Nobuo Suzuki vond in de inleiding van zijn boek: Wabi Sabi – The Wisdom in Imperfection.

Ik deel het hier:

Drie principes

Wabi Sabi beschouwt dingen die op de natuur lijken als mooi en kan worden samengevat met de volgende drie principes:

- Niets is perfect,

- Niets is af,

- Niets duurt eeuwig.

Toegepast op mensen

Pas principe 1 toe:

Bewust zijn van onze onvolmaaktheid maakt ons nederig; het accepteren ervan bevrijdt ons van ongezond veeleisend zijn en van de fixatie op een perfectie die in de natuur niet bestaat en daarom ook niet in de mens.

Het accepteren van onze eigen imperfectie en ieders unieke aard (en imperfectie!) betekent niet dat we daarin moeten berusten. Integendeel, het toont ons de weg die we moeten volgen om als mens te evolueren. Iedereen die denkt perfectie te hebben bereikt, heeft het bij het verkeerde eind – er is altijd ruimte voor verbetering – en het ontbreekt hen aan flexibiliteit, want veilig in hun absolute en subjectieve waarheid, hebben ze geen ruimte voor groei. Zo iemand is star en versteend en straalt geen leven uit1.

Pas principe 2 toe:

Als we verder gaan met het tweede principe, herinnert wabi sabi ons er precies aan dat niets af is. Net zoals de natuur zich oneindig ontwikkelt, te midden van cycli van geboorte en dood, zo is ook de mens dynamisch.

Een wabi sabi-benadering van het leven aannemen betekent, als je eenmaal je eigen onvolmaaktheid hebt erkend, continu leren omarmen en aannemen dat alles nog gedaan moet worden, en daarom dat alles nog geleefd moet worden.

Pas principe 3 toe:

Het derde principe van wabi sabi is het begrijpen van de vluchtige aard van alles wat bestaat, een concept dat ons terugvoert naar zen. Zoals de Boeddha ooit opmerkte toen hij het over lijden had, is een van de oorzaken dat mensen willen dat dingen die van nature van voorbijgaande aard zijn, permanent zijn.

Jeugd vliegt en wordt volwassenheid en dan ouderdom. Die fantastische televisie die je net hebt gekocht, doet het uiteindelijk niet meer of raakt verouderd. Die persoon die zo charmant en grappig leek, verrast ons niet meer, of misschien beginnen we uit elkaar te drijven omdat we, als twee takken van een boom, in tegengestelde richtingen zijn gegroeid. In plaats van ons droevig te worden, inspireert de acceptatie dat niets eeuwig duurt ons om de schoonheid van het moment te waarderen, wat het enige is dat we hier en nu kunnen vastleggen. Het is een uitnodiging om alles te geven wat we ook doen.

Dat is de magie van wabi sabi, die ons leven inspireert en ons een nieuwe horizon van gevoeligheid, groei en zelfontplooiing biedt.

To zover Nobuo Suzuki.

Wabi en Sabi volgens Omar Itani

Wabi sabi is een concept dat ons aanspoort om constant naar de schoonheid in imperfectie te zoeken en de meer natuurlijke cyclus van het leven te accepteren. Het herinnert ons eraan dat alle dingen, inclusief wijzelf en het leven zelf, vergankelijk, onvolledig en onvolmaakt zijn. Perfectie is dus onmogelijk en vergankelijkheid is de enige weg.

Afzonderlijk genomen zijn wabi en sabi twee afzonderlijke concepten:

Wabi

Wabi gaat over het herkennen van schoonheid in nederige eenvoud. Het nodigt ons uit om ons hart te openen en ons los te maken van de ijdelheid van het materialisme, zodat we in plaats daarvan spirituele rijkdom kunnen ervaren.

Sabi

Sabi houdt zich bezig met het verstrijken van de tijd, de manier waarop alle dingen groeien, verouderen en vergaan, en hoe dit zich prachtig manifesteert in objecten. Het suggereert dat schoonheid verborgen zit onder de oppervlakte van wat we werkelijk zien, zelfs in wat we aanvankelijk als gebroken beschouwen.

Wabi-Sabi

Samen creëren deze twee concepten een overkoepelende filosofie voor het benaderen van het leven:

- Accepteer wat is,

- blijf in het huidige moment en

- waardeer de eenvoudige, voorbijgaande levensfasen.

De eerste leer van de wabi sabi-filosofie is om dankbaarheid en acceptatie te oefenen.

Het gaat niet om opgeven. Het gaat erom je over te geven aan de ernst van de situatie en vervolgens actief een rol te spelen bij het beslissen wat er daarna gebeurt.

Amor Fati

Het is vergelijkbaar met wat de stoïcijnen Amor Fati noemden, een liefde voor het lot. En wabi sabi predikt hetzelfde: je zult vrede en vrijheid vinden, en je zult het pad van groei betreden, zodra je begint toe te geven en je over te geven aan de onvolmaakte stroom van het leven.

Als alles in de natuur altijd verandert, kan niets ooit absoluut compleet zijn. En aangezien perfectie een staat van volledigheid is, kan niets ooit perfect zijn. Daarom leert de wabi sabi-filosofie ons dat alle dingen, inclusief wijzelf en het leven zelf, vergankelijk, onvolledig en onvolmaakt zijn. Het probleem is echter dat onze gebrekkige manier van denken ons begrip van wat perfectie werkelijk is, heeft vertroebeld.

Open een thesaurus en zoek naar de antoniemen voor “perfect” en je zult de volgende woorden vinden:

- gebrekkig,

- corrupt,

- inferieur,

- arm,

- tweederangs,

- onbeholpen,

- gebroken,

- verkeerd,

- slecht…

Al deze negativiteit. Geen wonder dat we zo geobsedeerd zijn geraakt door het zoeken naar perfectie.

Om dit negatieve stigma rond imperfectie te elimineren, moeten we het eerst volledig afwijzen als zijnde “het tegenovergestelde” van dat fictieve construct dat perfectie is.

We moeten een nieuw verhaal schrijven dat luidt: Imperfectie is geen compromis; imperfectie is de enige manier omdat imperfectie de ware aard van de dingen is.

De leer van de wabi sabi-filosofie is eenvoudig: streef niet naar perfectie, maar naar uitmuntendheid. Met andere woorden, doe gewoon je best om de beste te zijn die je kunt zijn. Alle dingen in het leven, ook jij, bevinden zich in een onvolmaakte staat van verandering. Verandering is de enige constante. Alles is van voorbijgaande aard en niets is ooit compleet. En daarom bestaat perfectie niet.

Kintsugi

Een eeuwenoude vorm van kunst komt voort uit wabi sabi, waarbij je kapotte voorwerpen repareert met gouden vullingen, waardoor ze ‘gouden littekens‘ krijgen. Het staat bekend als Kintsugi.

Denk aan een kom of theepot die op de grond is gevallen. Wat zou jij er mee doen? Je zou hoogstwaarschijnlijk de stukken oppakken en weggooien. Maar niet met Kintsugi.

Hier breng je de stukjes gebroken aardewerk weer bij elkaar en lijm je ze vast met vloeibaar goud.

Zou ze dat niet onvolmaakt, permanent en onvermijdelijk gebrekkig maken, maar op de een of andere manier mooier?

Kintsugi herinnert ons eraan dat er grote schoonheid schuilt in kapotte dingen, omdat littekens een verhaal vertellen. Ze tonen standvastigheid, wijsheid en veerkracht, verdiend door het verstrijken van de tijd. Waarom deze onvolkomenheden of gouden littekens verbergen als het de bedoeling is dat we ze vieren?

Het idee hier is simpel: er zullen vele keren in je leven zijn dat je je gebroken zult voelen. Er zullen gebeurtenissen zijn die emotionele of fysieke littekens zullen achterlaten. Verstop je niet in de schaduw van je eigen zonneschijn. Dim je eigen licht niet met de duisternis van een wolk. Laat die littekens in plaats daarvan opnieuw tekenen met goud.

Bedenk dat je mislukkingen er zijn om je te leren hoe je dingen niet moet doen, je fouten zijn er om je het belang van vergeving te leren, en je rimpels zijn er om je te herinneren aan de lach die ze veroorzaakte.

Tsukubai

In de buurt van het theehuis bij de Ryoanji-tempel in Kyoto is een beroemd stenen waterbassin, waar voortdurend water doorheen stroomt voor rituele zuivering. Vanwege de lage hoogte van het bassin moet de gebruiker bukken om het te gebruiken, als teken van eerbied en nederigheid.

Op deze 17e-eeuwse tsukubai (waterbassin) staat een oude inscriptie met vier Chinese karakters:

五, 隹, 止, 矢.

Alleen gelezen, zijn deze karakters niet van belang. Maar in combinatie met de randen van het centrale plein worden ze:

吾, 唯, 足, 知

en kunnen ze worden gelezen als “ware, tada taru (wo) shiru” wat betekent “Ik weet alleen veel” of “Ik ken alleen tevredenheid.”

De tsukubai belichaamt ook een subtiele vorm van Zen-onderwijs met behulp van ironische juxtapositie: terwijl de vorm een oude Chinese munt nabootst, is het sentiment het tegenovergestelde van materialisme. Zo heeft de tsukubai gedurende vele eeuwen ook gediend als een humoristische visuele koan voor talloze monniken die in de tempel woonden, en hen dagelijks zachtjes te herinneren aan hun gelofte van armoede.

“Ik ken alleen tevredenheid” is tevreden zijn met de emotie of woede, net zoals je gewoonlijk tevreden bent met de emotie van opwinding. Tevreden zijn met de staat van verdriet, net zoals je tevreden bent met de staat van geluk.

Maar hoe zit het met een meer poëtische vertaling van die inscriptie?

Hoe zit het met, “Rijk is de persoon die tevreden is met wie hij is of wat hij heeft.”

Of wat dacht je hiervan: “Wat ik heb is alles wat ik nodig heb.”

Zie je, de wortel van alle ongeluk wordt geboren uit ontevredenheid met wie of waar je bent en wat je hebt. Zo simpel is het echt.

In zekere zin leert wabi sabi ons om de meest elementaire, natuurlijke objecten interessant, fascinerend en mooi te vinden. Vervagende herfstbladeren zouden een voorbeeld zijn. Wabi sabi kan onze perceptie van de wereld zodanig veranderen dat een chip of barst in een vaas het interessanter maakt en het object meer meditatieve waarde (uniekheid) geeft. Evenzo worden materialen die verouderen, zoals kaal hout, papier en stof, interessanter omdat ze veranderingen vertonen die in de loop van de tijd kunnen worden waargenomen.

Wabi Sabi Haiku

Sommige haiku’s in het Engels nemen ook de wabi sabi-esthetiek over in geschreven stijl, waardoor losse, minimalistische gedichten ontstaan die eenzaamheid en vergankelijkheid oproepen, zoals deze:

“autumn twilight:

the wreath on the door

lifts in the wind“.

1 Exude life: het beste uit het leven halen! Of, zoals in mijn motto: One Life, live one.